by Jordan Larimore

ST. LOUIS - How are you helping prevent suicide? It’s a question more than 40,000 Mercy co-workers can now answer, having completed a Zero Suicide Initiative that launched in recent years.

“It’s not something somebody is telling us we have to do,” said Dr. Douglas Walker, an internationally renowned Mercy clinical psychologist based in New Orleans who serves in an outreach role for Mercy. In 2018, he began the effort of establishing Mercy as a Zero Suicide Initiative organization.

“There are no government directives or other rules around organizations or companies doing something proactive to decrease suicides,” he said. “It has never been more critical, with suicide deaths rising in many of our states. Behavioral health should be treated no differently than any other physical health issue. It’s a major part of a person’s overall health even though some symptoms can’t be seen visually.”

Dr. Walker worked with the Zero Suicide Institute, a division of the Educational Development Center, a global nonprofit that works to improve education, promote health and expand economic opportunity. Founded in 1958, the group has worked on behavioral health programs in 80 countries around the world.

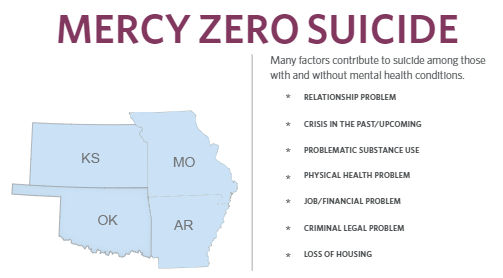

Unfortunately, suicide rates have increased in recent years, including those where Mercy primarily operates. In fact, more than 49,000 people died by suicide in 2022, making it the 11th leading cause of death. Additionally, in 2022 there was an estimated 1.6 million suicide attempts.

All four states were within the 21 highest suicide rates in the country, and the overall rate among them is nearly 39% higher than the national average, according to the same CDC data.

Kirsten Sierra is Mercy’s Zero Suicide coordinator and chairs a suicide subcommittee Dr. Walker founded. Her position is based in Mercy’s quality and safety department, where suicide prevention is thought of no differently than infection prevention or other patient safety measures. She says with patients, the challenge is making sure they’re prepared once they leave Mercy’s care, because suicide risk can change over time.

“We want people to know what to do and what to watch for when they leave our facilities,” Sierra said. “When you screen someone, you’re screening them at one point in time. Suicide risk fluctuates, often rapidly. So with a plan in hand, people are prepared and not caught off guard when their mood changes or hits a low. First, we show them how to how to recognize when they may be in crisis and how to deescalate that crisis themselves, and second, how to reach out for help if things go off the tracks and they are in crisis again. Third, we help them to think through ways to make their environment safer. We give them an action plan they can put in motion on their own. It gives them some sense of independence to know what to do.”

Clinicians in other specialties often discuss their own symptoms to their peers in casual conversation, such as a cardiologist asking an orthopedic specialist about a sore shoulder or knee. Never, though, Dr. Walker said, do colleagues ask him about their mental health upon finding out that he’s a psychologist.

“There is a stigma attached to it,” he said. “It’s very unfortunate that as a society we believe a broken heart is different than a broken arm. And maybe it’s because you can’t see it, at least most of the time. I’ve got stuff that I deal with, my family’s got stuff, we’ve all got our stuff that we deal with, and somehow we think that we’re lesser for it, but I can tell you, I’ve met some of the strongest people I’ve ever met right here in my office.”

Referrals to Mercy Behavioral Health or community resources are available 24 hours a day. Call us at 314-251-0555. If you or someone you know needs support now, call or text 988. Or go here for additional resources and video on mental health.